IRENE HRAFNAN

HLIÐRUN / PARALLAX

22.06 – 16.07

Irene Hrafnan sýnir verk sem unnin voru í samtali við verk og sögulega arfleifð Gunnfríðar Jónsdóttur myndhöggvara og vinnustofu hennar og heimili að Freyjugötu 4. Sýningin stendur yfir í Gryfjunni dagana 22. júní - 16. júlí.

Hliðrun.

Hliðrun á hugtaki eða hlut, á tíma, á sögulegu samhengi.

Hliðrun á valdastöðu.

Hliðrun á kyni.

Hliðrun á stéttarstöðu, tungumáli, skynjun, upplifun.

Hliðrun á húsi.

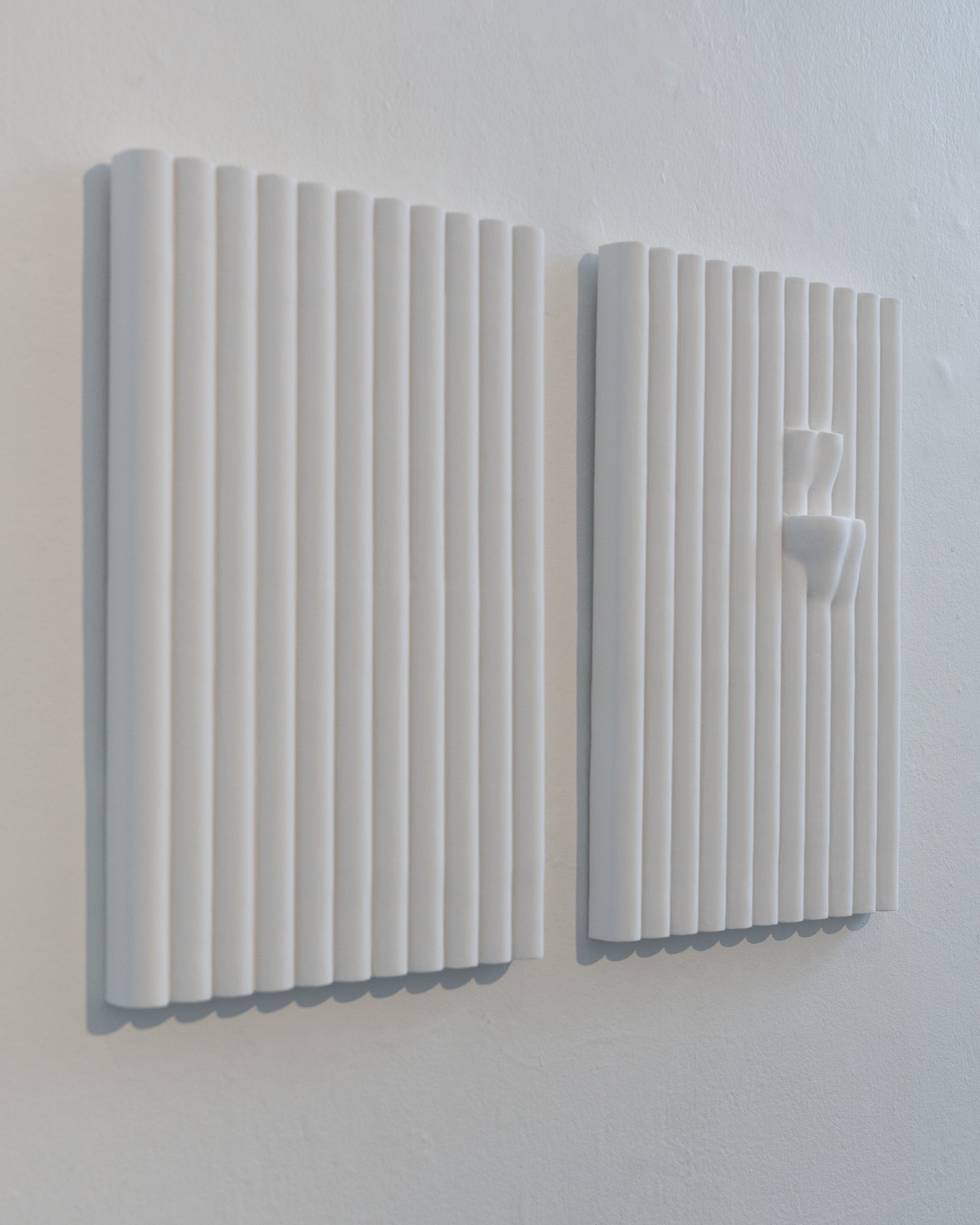

Þegar Gunnfríður Jónsdóttir og Ásmundur Sveinsson skildu skiptu þau húsinu í tvennt með því að draga línu eftir því endilöngu. Gunnfríður fékk aftari hluta hússins og Ásmundur fremri rýmin og sýningarsalinn. Þegar húsinu var skipt upp urðu til landamæri eða skil sem endurskilgreindi ekki bara þeirra samband heldur einnig samband fólks við rýmið. Skilin hafa komið fram í veggjum, læstum hurðum og jafnvel lúmskari afmörkunum. Skipting á rými breytir rýmisskynjun og krefst aðlögunar og umbreytingar á líkamlegu og andlegu rými. Inngrip sem líkast til leiddi til endurstillingar á húsgögnum og lýsingu og hefur þar með haft áhrif á samskipti þeirra við umhverfið. Það er ákveðin tvíhyggja sem felst í hugmyndinni að skipta húsi í tvo hluta, andstæður sem myndast við þetta byggingarfræðilega inngrip. Tvískipting sem vísar ekki einungis til aðskilnaðar heldur ennig til sambúðar og samspils tveggja andstæðra þátta.

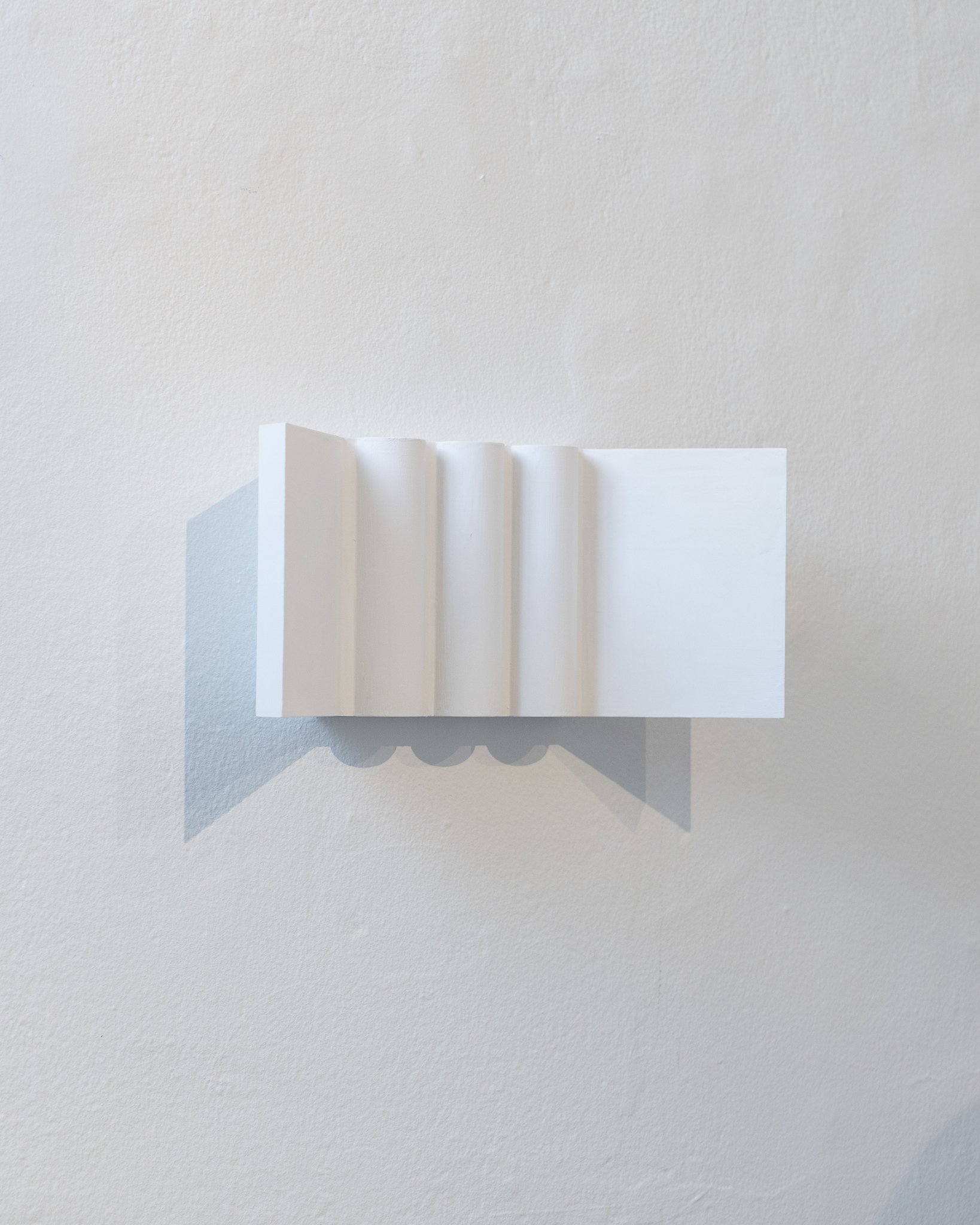

Gangar og stigarými eru tenging líkamans við önnur rými hússins og hafa innbyggðan takt og tíma. Upphaflega voru þessi rými tenging á milli fremri og aftari hluta hússins sem og á milli herbergja og hæða, en um tíma voru lokaðar hurðar og veggir á hverri hæð. Í formrænu sinni og efni spegla þau líkamann einnig á efnislegan hátt með útlínum sem bera vitni um samlífi byggingar og líkama. Beygjur og form stigaops, sem minna á mannleg form, gætu að hætti vestrænnar tvíhyggju verið álitin kvenleg, þar sem hugur og líkami hafa ranglega verið sett fram sem andstæðupar, hugurinn karllægur og líkaminn tengdur hinu kvenlega. Líkaminn er þó ekki kynbundin vera heldur skynjandi vera eða skynfæri. Beygjur og flæðandi línur stigaops vekja tilfinningu fyrir flæði og náttúrulegum takti sem speglar hreyfingu líkama sem fer upp eða niður. Stefnulínur innan stigaopsins marka hreyfingu í ákveðna átt og formin leiða augað og líkamann og skapa tilfinningu fyrir frásögn innan rýmisins. Lögun herbergja mótar látbragð okkar og hefur áhrif á líkamsstöðu, eins og rúmfræðin sjálf verði samstarfsaðili í kóreografíunni. Ólíkt göngum og stigum sem stýrast af hreyfingu og tíma þá eru þessi rými kyrrstæð, ekki ólíkt höggmyndum sem eru varanleg mannvirki líkt og byggingar. Kyrrsstæðir líkamar í hvíld. Líkamar þar sem aldrei er breytileg fjarlægð á milli tveggja punkta og hver líkamspartur, hvert rými og hvert herbergi verður að staðsetingu eða áfangastað í sjálfu sér.

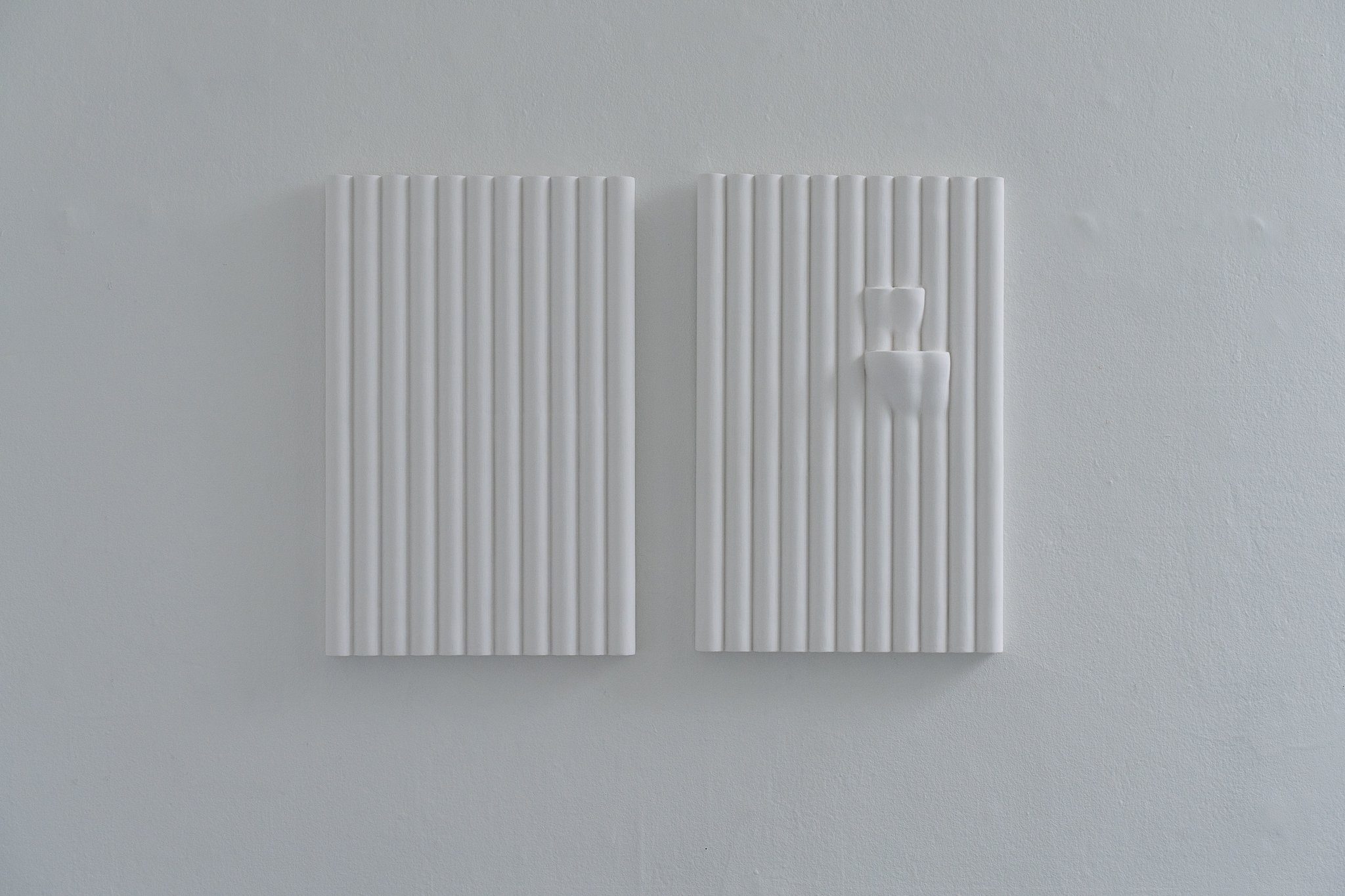

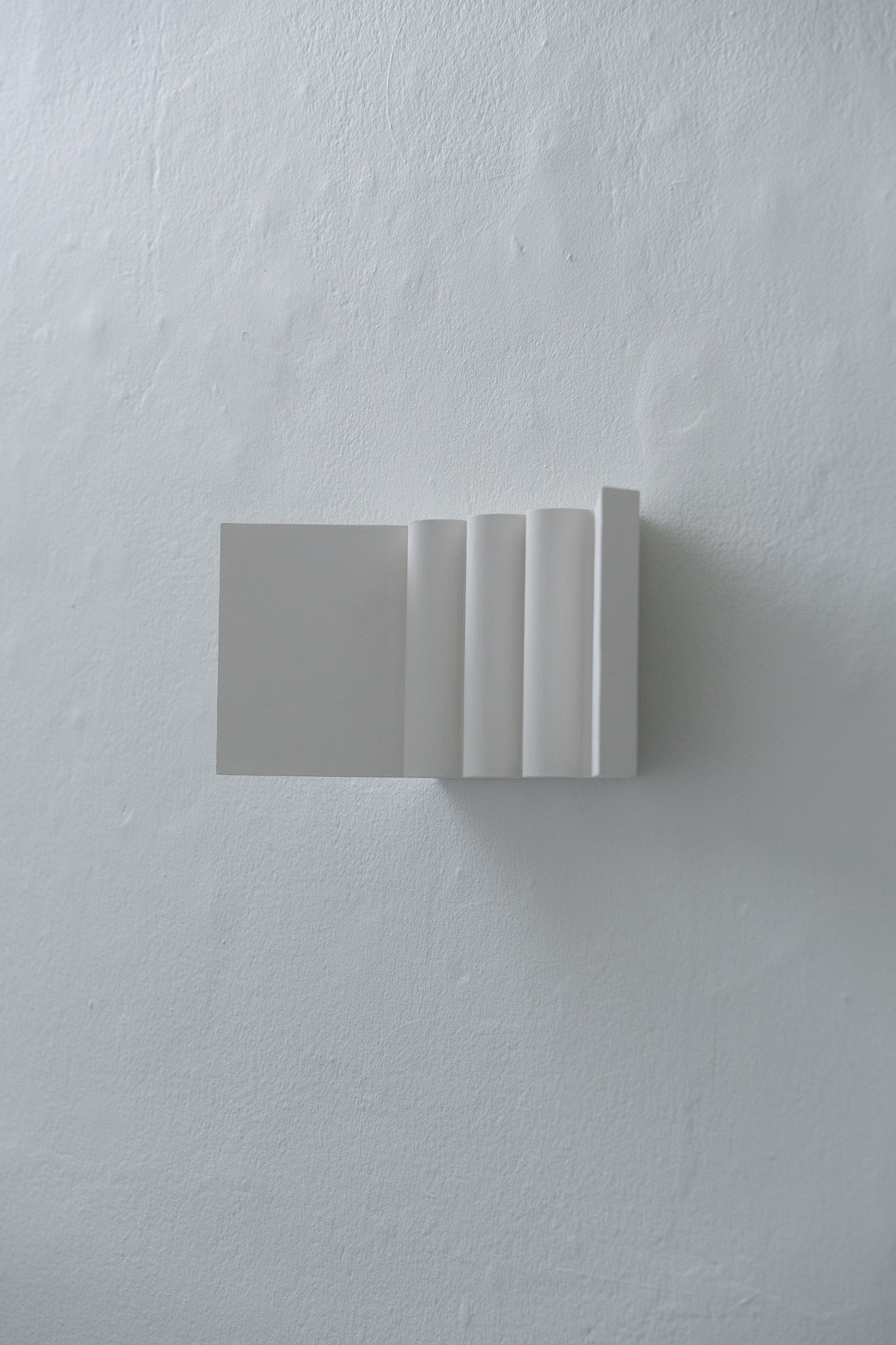

Irene Hrafnan (f. 1983) lauk BA námi í myndlist við Listaháskóla Íslands árið 2007 og Master of Fine Arts frá School of Visual Arts í New York árið 2010. Verk sín vinnur Irene gjarnan út frá rýmislegum vangaveltum arkitektúrs, efnis og forms en þau vísa á sama tíma til mannlegrar tilvistar og sögulegs tengslasamhengis. Verkin kanna sambandið milli upplifunar á rými og ímyndaðs rýmis, sem og samband manneskjunnar við umhverfi sitt. Með því að skapa spennu á milli líkamlegrar upplifunar og speglaðrar tilveru endurskapa verkin ný rými og reyna á skynjun áhorfandans á þeim. Verkin vinnur hún í ýmsa miðla, þar á meðal skúlptúra, myndverk, videoverk og texta. Verk hennar hafa verið sýnd á Íslandi, í Evrópu og í Bandaríkjunum.

Gunnfríður Jónsdóttir (26. desember 1889 - 15. maí 1968) var ein af fyrstu kvenkyns myndhöggvurum Íslands. Hún kynntist Ásmundi Sveinssyni í Reykjavík og árið 1919 urðu þau samskipa til Kaupmannahafnar, en það var upphafið að 10 ára dvöl hennar erlendis. Þau Ásmundur voru gefin saman í hjónaband árið 1924 og vann Gunnfríður fyrir þeim sem saumakona á meðan Ásmundur lagði stund á listnám í Stokkhólmi og París. Gunnfríður var orðin fertug þegar hún gerði sína fyrstu höggmynd en hún bjó og starfaði í aftari hluta hússins eftir skilnaðinn og var vinnustofa hennar í Gunnfríðargryfju. Gunnfríði voru kvenskörungar íslenskra sagna hugleiknir, en meðal verka hennar er Landsýn minnisvarði við Strandakirkju um kraftaverkið í Engisvík, sem sýnir hvítklædda konu benda sjómönnum í sjávarháska inn í víkina og Landnámskonan við Tjörnina, sem talið er tengajst minningu tveggja íslenskra kvenna, Hallveigar Fróðadóttur og Auðar djúpúðgu. Verkið vísar einnig til landnámskvenna í víðtækari merkingu og þá ekki síst til kvenna í heimi listanna, þar á meðal Gunnfríðar sjálfrar.

IRENE HRAFNAN

PARALLAX/HLIÐRUN

22.06 – 16.07

Parallax.

Parallax of concepts or objects, of time, of historical context.

Parallax of power positions.

Parallax of gender.

Parallax of social status, language, perception, experience.

Parallax of a house.

When Gunnfríður Jónsdóttir and Ásmundur Sveinsson divorced, they divided the house in two by drawing a line through it lengthwise. Gunnfríður got the rear part of the house, while Ásmundur the front spaces and the exhibition hall. The division of the house created boundaries that not only redefined their relationship but also people's relationship to the space. The dividing became apparent in walls, locked doors, and even more subtle delineations. The dissection of space alters the perception and requires adaptation and transformation of physical and mental spaces. The intervention most likely led to rearrangement of furniture and lighting, thus impacting their interaction with the space. There is a certain duality inherent in the idea of dissecting a house into two parts, opposing elements that arise from this architectural intervention. The duality refers not only to separation but also to cohabitation and interaction of two opposing factors.

Corridors and staircases serve as connections between the body and other spaces of the house, possessing inherent rhythm and time. Initially, these spaces served as connections between the front and rear parts of the house, as well as between rooms and floors. However, over time, doors and walls were closed on each level. In their form and substance, they also reflect the body in a material way, with outlines that bear witness to the coexistence of the body and the structure. Curves and shapes of staircases, resembling human form, could, in a western dualistic manner, be considered feminine, as the mind and body have mistakenly been presented as opposing pairs, the mind being masculine and the body being linked to the feminine. However, the body is not a gendered being but rather a perceiving entity or sensory organ. Curves and flowing lines of staircases evoke a sense of flow and natural rhythm, mirroring the movement of the body as cending or descending. Directional lines within the staircase denote movement in a specific direction, and the shapes guide the eye and body, creating a sense of narrative within the space. The layout of rooms shapes our gestures and influences our bodily posture, as if the geometry itself becomes a collaborator in the choreography. Unlike corridors and staircases, which are ruled by movement and time. These spaces are static, not unlike sculptures that, like buildings are fixed structures. Motionless bodies at rest. Bodies where the distance between two points never wavers, and each body part, each space, and each room becomes a location or destination in itself.

Irene Hrafnan Bermudez (born 1983) completed her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at the Iceland Academy of the Arts in 2007 and received a Master of Fine Arts from the School of Visual Arts in New York in 2010. Irene often works with spatial reflections on architecture, material, and form, simultaneously referencing human existence and historical contexts. Her works explore the relationship between the perception of physical space and imagined space, as well as the connection between individuals and their surroundings. By creating tension between bodily experience and reflected existence, her works reconstruct new spaces and challenge the viewer's perception. She employs various media in her art, including sculpture, installations, video art, and text. Her works have been exhibited in Iceland, Europe, and the United States.

Gunnfríður Jónsdóttir (December 26, 1889 - May 15, 1968) was one of the first female sculptors in Iceland. She met Ásmundur Sveinsson in Reykjavík, and in 1919, they traveled to Copenhagen, which marked the beginning of her 10-year stay abroad. Gunnfríður and Ásmundur got married in 1924, and while Ásmundur pursued art studies in Stockholm and Paris, Gunnfríður worked as a seamstress to support them. Gunnfríður was in her forties when she created her first sculpture and lived and worked in the rear part of the house after their divorce, with her workshop in Gunnfríðargryfja. Gunnfríður's works were inspired by women from Icelandic sagas, and among her notable pieces are „Landsýn“ a monument by Strandarkirkja about the miracle in Engisvík, depicting a white-clad woman gesturing to fishermen in distress entering the fjord, and "Landnámskonan“ við Tjörnina," which is believed to be related to the memory of two Icelandic women, Hallveig Fróðadóttir and Auður djúpúðga. The artwork also alludes to the pioneering women in a broader sense, particularly women in the art world, including Gunnfríður herself.